|

|

Post Last Edit by lizz_7777 at 1-5-2010 17:53

The Odyssey of a Forgotten Nation, The Moriscos of Spain (Pt 1)

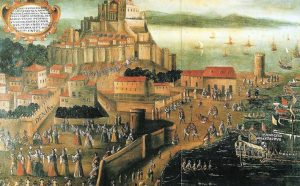

Four hundred years ago, on precisely October 2nd, of the year 1609 CE., in the Iberian peninsula, the Spanish fleet escorted a diverse array of ships of many European nations from the port of Denia on the southeastern coast of modern day Valencia, in Spain, in a land that was once known as al-Andalus. The fleet’s destination was multiple landing ports in predominantly Muslim North African shores. It was the first shipment of deported Spanish Muslims who lived there for over a hundred and twenty years after the fall of Muslim Spain in Granada back in 1492 CE. These Muslims were known in history by their Spanish title the “Moriscos”, whose ancestors lived and ruled in al-Andalus (Spain and Portugal) for more than 800 years, creating one of the greatest and most exquisite civilizations Europe had ever seen.

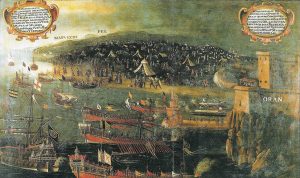

The ships were brought from all over Europe and carried that day, according to Spanish documents, around 5,300 Morriscos. They embarked on September 30th, and remained in transit until they set off on October 2nd, and after a rough trip, they arrived at the Spanish fortified military settlement in Oran (modern day Wahran in Algeria) on October 5, 1609.

This first shipment was the beginning of five years of systematic expulsion of a whole ethnic population, or nation, that varied in number according to different records from 250,000 to over a million. For over five years the Moriscos were expelled forcibly from a land they once called home, and the only home they had ever known. The reason for their expulsion was that they were perceived by the Spanish monarchy, who became the new rulers of the land, as different. It was a sad and brutal reality, a human genocide and a systematic ethnical cleansing the like of which Europe had never experienced before. It was the end of an episode in “The Odyssey of a Forgotten Nation, The Morriscos of Spain.” And this is their story.

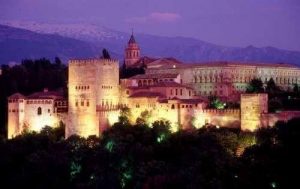

Their odyssey started on the day when Abu Abdillah as-Saghir (Boabdil in European resources), the last governor of the last Muslim kingdom in al-Andalus, signed the capitulation of Granada in November 25, 1491 CE. and then submitted the keys of his kingdom to Ferdinand and Isabel, king and queen of Aragon and Castile, in January 2nd, 1492. The treaty was suppose to guarantee a set of rights to the Muslim inhabitants of the surrendered city, known back then as the moors; rights including religious tolerance and fair treatment in return for their unconditional surrender and submission.

The treaty contained many articles among which were the following: - That all people should be perfectly secure in their persons, families, and properties.

- That they should be allowed to continue in their dwellings and residences, whether in the city, the suburbs, or any other part of the country.

- That their laws should be preserved as they were before, and that no-one should judge them except by those same laws.

- That their houses of worship (masajid), and the religious endowments (awqaaf) appertaining to them, should remain as they were in the times of Islam.

- That no Christian should enter the house of a Muslim, or insult him in any way.

- That all those who might choose to cross over to Africa should be allowed to take their departure within a certain time, and be conveyed in the king’s ships, and without any pecuniary tax being imposed on them, beyond the mere charge for passage.

- That the Christians who had embraced Islam should not be compelled to relinquish it and adopt their former creed.

- That no Christian should be allowed to peep over the wall, or into the house of a Muslim or enter a masjid (mosque).

- That any Muslim choosing to travel or reside among the Christians should be perfectly secure in his person and property.

- That no muadhin (one who calls for the prayers) should be interrupted in the act of calling the people to prayer, and no Muslim molested either in the performance of his daily devotions or in the observance of his fast, or in any other religious ceremony; but that if a Christian should be found laughing at them he should be punished for it.”

The treaty must have been perceived by the Christians of that time as very generous, and indeed it was, however and unfortunately, it did not last long enough for the ink even to dry. In less than ten years and before the end of the decade, signs of tension started to arise in Granada. The tolerant policy, both civil and religious, of the first administration assigned to run the newly conquered city, seemed to the more zealots Christian crowd not working at all, and therefore was replaced in 1498 with a new administration and a new strict policy. Inquisitor general Archbishop Cisnero of Toledo arrives in Granada in 1499 with new confrontational and intolerant policies of change and forcible conversion. His policies were, to certain limit, backed by the desire of the monarchy to create and maintain a homogenous Spanish society in both politics through ensuring people’s loyalty to the Crown, and faith by adapting Catholicism as religion. There was no doubt a policy of that kind would have dangerous and detrimental consequences, and therefore it caused the first spark of the flame, and the atrocity began.

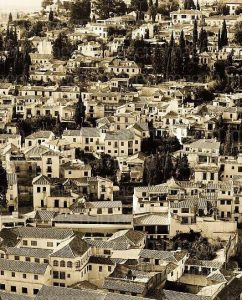

A case of murder and its aftermath in the year 1500, lead to street fight between the Muslims in Albaicin, the Muslim quarter of Granada, and the royal authority. After few days of rioting, the crisis was contained but the damage has already been done and it became permanent; it drew great suspicion and caused great mistrust between the two groups. The original treaty was now considered breached regardless of who caused it, and the new administration became free to impose any new terms it saw fit.As a result of this new development, the forcible conversion to Catholicism was imposed on more than 50,000 souls of the inhabitants of Granada, which was one of the most detrimental punitive punishments Cisnero was able to first achieve in his career. The Muslims were subsequently forced into hiding, and thus began the period of Crypto- and clandestine practice of Islam. This period marked the beginning of the Moriscos era in the history of Spanish Muslims. Now that they are no longer Muslims, openly at least, the terms of the original capitulation of Granada could not be applied to them and a new treaty was introduced with much more demands from the newly converted to change and assimilate into the society.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Post Last Edit by lizz_7777 at 1-5-2010 17:49

The Muslims of Spain now were divided into three groups: the Mudejars, the Granadas and the Moriscos. The Mudejars were Muslims who lived under Christian rule, in some areas for over few centuries, in the land of Castile and Aragon and other territories retrieved earlier from the hands of the Muslims during the reconquista, prior to the fall of Granada. They spoke Castilian as their first language, they lived life similar to the life of the Muslims in the West today, they participated in the different aspects of life, and were considered loyal subjects to the crown. They enjoyed many privileges as citizens of the land and cities were they lived.

The Granadans were the original Muslims of the late kingdom of Granada, who spoke Arabic as their first language and who were not affected by the conversion followed the revolt of Albaicin. They came from different social classes and lived mainly in the former region of the kingdom of Granada. Then there were the Moriscos, the newly converted to Catholicism, but in many cases remained secretly faithful to their original religion al-Islam.

Not too long after that and in February of 1502, the forcible conversion became a state policy, and forced on all the Muslims, including the long privileged Mudajers, and the remaining Jews of Spain. Religious and civil authorities continued pursuing it throughout the century on different occasions, particularly following every revolt that took place until the last day of the expulsion.

Although the Moriscos were now considered Christians, officially at least, they have always been treated differently, particularly by the general public who always viewed them as rivals rather than fellow Christians. Even those Moriscos who tried hard to prove their good Christian character, they were never fully accepted by their fellow old Christians. In response to that attitude, the Moriscos became introversive and pushed further into clandestine lifestyle.

Despite the authorities’ effort to displace them, sending them deep into the Iberian peninsula and moving the old Christians to live amongst them, to ensure their complete merge into the society, the Moriscos continued preserving their unique identity.

The identity crisis of the Moriscos was obvious throughout their entire history. They were faced with few and limited options, the easiest of which was still troubling and dangerous for many. Their options were: 1) Hijra or immigration to the heartland of the Muslim world and particularly in North Africa. This option was an opened window, at least in the first few years following the fall of Granada and during the first period of the forcible conversion, or 2) Assimilation and completely dissolving into the Castilian, Catholic society. No doubt this was the optimal option preferred by the state, or 3) Coexistence, and that is to live along the side of their fellow non-Muslim neighbors like the Mudajer did for many generations. For the Moriscos, of all the available options, coexistence would probably have been their best option. They tried to achieve coexistence as a mean of survival, but the state’s policy aforementioned and the pressure from the religious institutions, such as the Holy Office of Inquisition, caused their efforts to go to no avail.

Soon after the suppression of the 1568-1571 revolt of the Moriscos which synched in time with the marine battle of Lepanto, in which the Ottoman navy lost its supreme and ultimate control of the mediterranean to Spain, creating a power shift and a new balance in the region, the crown turned back inward to solve the Moriscos problem once and for all. The loss of the Ottomans in Lepanto opened a new window to the Spanish fleet in the Mediterranean. The shores of North Africa were no longer protected and became more accessible; sentiments of rejection for the Moriscos were at their hight, and thus the expulsion proposal prevailed. Although expulsion since then had become inevitable, but it would take the Spanish authority few more decades to put it into action. An operation of such a massive size was far beyond the Spanish monarchy to achieve without foreign aid. Therefore, and with the help of the Vatican and other European nations, King Philip III became adamant that deportation was the safest and only solution for the preservation of the Spanish way of life. He issued the edicts of expulsion which effectively began in September of 1609, executed in October the same year and continued until the last official shipment in 1614.

This was only a cursory look at the historical context of the Moriscos crisis, and there is no doubt the dynamics which contributed to the crisis were far more complex than those presented here. But what was the condition of the Moriscos during this long period of time? What happened to them? And what caused their tragedy?Today, what can we, as western Muslims, learn from their experience? In the rising ethnical and religious tension in the world, while living all over the earth in a culture of globalization, where traditional boundaries are no longer visible or protected, how can we avoid another odyssey from happening to the massive numbers of Muslims and non-Muslims alike?The answer will be coming in part two. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|